What's the face value of a World Series ticket? *Shrug emoji*

Media and lawmakers are concentrating on astronomical resale prices, but the lack of transparency over base fees is also a problem

World Series frenzy has hit Toronto and Canada as the Blue Jays earlier this week won their way into the fall classic for the first time in 32 years. And, as happens with every big live event these days, fans are fuming over astronomical ticket prices.

The outrage has been loud enough to get Doug Ford’s attention. The Ontario Premier, who in 2019 axed a law that would have capped ticket resale prices at 50 per cent above face value, is now saying he may reconsider that move.

“When you have one player in the market that controls the tickets, that’s not right for the people,” he told Queen’s Park reporters on Wednesday. “I just don’t believe in one company, and that’s what’s happening right now with Ticketmaster in my opinion.”

The big issue highlighted by much of the media coverage around this is how Ticketmaster handles resale on its website. High-profile concerts and sporting events regularly sell out fast thanks to what has been described as “industrial-scale scalpers,” who use armies of bots to buy up tickets and then immediately resell them at vastly inflated prices, also on Ticketmaster and other resale sites such as StubHub.

It happens so quickly that even the few lucky buyers who manage to squeeze through queues often don’t get there before the bots have snatched everything up, meaning the only tickets available to them are overpriced resales.

This scheme features as part of the U.S. Department of Justice’s current antitrust case to break up Ticketmaster’s parent Live Nation. The lawsuit draws on a joint hidden-camera investigation by the CBC and Toronto Star, which in 2018 caught Ticketmaster representatives admitting they were aware of scalpers using fake accounts to buy and resell tickets – and that they were fine with it.

Ticketmaster, after all, earns fees on every sale – original or resale – so the “industrial-scale” scalping is ultimately good for its business.

Likely realizing how much doo-doo it’s now in, Live Nation last week sent a letter to U.S. lawmakers promising to crack down on scalping. We’ll see how that goes.

What isn’t getting nearly as much attention, especially in this case of the Blue Jays and the World Series, is the face value of tickets. Or rather, the lack of it.

The Blue Jays have not publicly disclosed face values. Queries to the team, its owner Rogers, and Ticketmaster have not been returned while multiple phone calls to the team’s ticket office did not get through. Not even ChatGPT could find any record of face values:

It’s worth nothing that, as despised as they are by Blue Jays fans, the New York Yankees were at least publicly posting face-value prices online while they were still in the playoffs.

The base prices paid by the comparatively few real humans who did get tickets are thus varying wildly depending on who they are and when they got them.

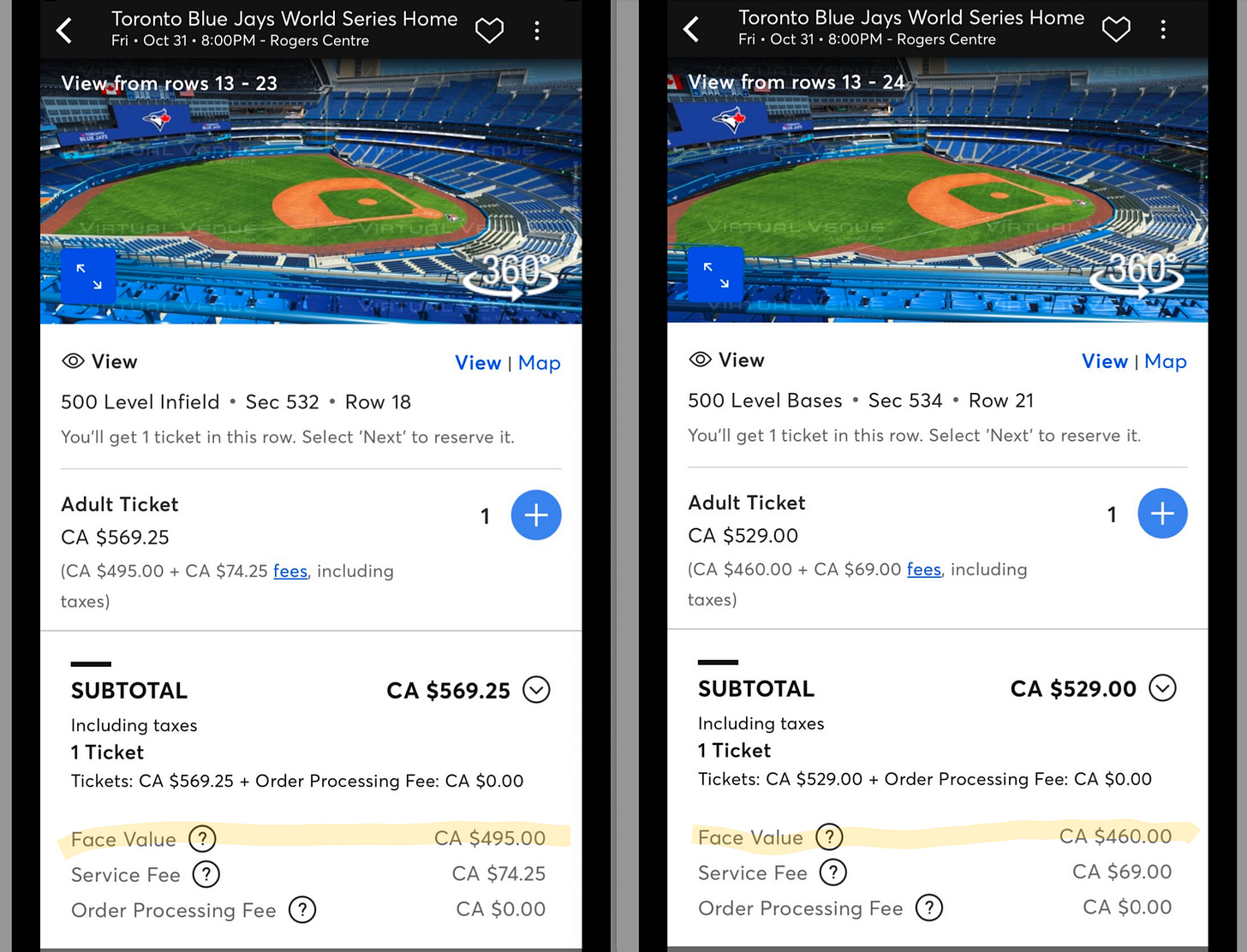

A buyer identified as Kadence told CTV News, for example, that she bought a pair of seats this week in the 500 level of the SkyDome… I mean Rogers Centre for $495 each plus fees and taxes. That jibes with screenshots other potential buyers shared on social media:

A friend of mine who is a season ticket holder tells me she bought two seats in the second row of the 500s right behind home plate – just about the best tickets on that level of the stadium – for a total of $214 each. She also bought an extra seat next to those two at full price without the season-ticket-holder discount, for a total of $287.

Another acquaintance tells me he bought a pair of tickets through an advance sale halfway up section 112, the ground level of the stadium, for $541 each, which is on par with the supposed face-value 500-level prices shown above.

Needless to say, 100-level seats are far more valuable – at least in theory – than nosebleeds so the differences, even given advance pricing, are head-scratchingly stark.

Keldon Bester, executive director of the Canadian Anti-Monopoly Project, says the opacity of actual ticket values even before resale is purposeful on the part of Ticketmaster and Rogers, with the companies having clear incentives to see prices go as high as possible.

“It’s the asymmetric nature of dynamic pricing that benefits the party with the most information,” he told Do Not Pass Go. “Individuals have a high barrier to understand what prices are available and to who and when, so they’re at an obvious disadvantage.”

This lack of information coupled with Ticketmaster’s tolerance and even encouragement of scalping means ticket prices aren’t reflecting a natural marketplace, but rather one that’s clearly broken in favour of sellers.

“When you bring highly sophisticated scalpers in and don’t enforce your own policies on them… they’re essentially rigging the market so that the prices are well beyond what people would normally pay.”

For what it’s worth, here are some pics of 1993 World Series tickets, which are being sold on eBay. Not only are these relics notable because they literally have face values printed on them, they also illustrate just how incredibly high current prices are:

By way of comparison, the Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator suggests the prices on these tickets should be about double in today’s dollars.

But next to the supposed face values on the comparable seats mentioned above, today’s prices are closer to between five and 10 times the rate of inflation. Go Jays?

The sad part is that most resellers (scalpers is not a great word) actually lose money. It’s only the market maker that comes out on top.

Thanks for writing this.